My mother is so good at being a mother and I know that because when we go on walks, I can point to any flower or tree and ask her what it is and she’ll almost always know the answer.

She loves to have things growing all around her. Is good at tending to them, and keeping them happy. I’ve wondered what I’ll say one day when I’m asked about the yellow flowers dotting the walking trail. Really, I’ve wondered when that whole thing “happens.” If, it just “happens.”

Mothers always seem to know of every living thing. With every reply of “that’s bougainvillaea”—I can never remember the bougainvillaea—or, with every glance I’ve ever taken of her in a one-piece bathing suit, crouching down into her garden in the heat of summer, pulling at the weed or two that caught her eye, I imagine her heels connecting to the wet earth below by knotty, thick tangles of roots.

She’s my favorite person to walk with because she always takes long looks up and around. Stops to pick a piece of honeysuckle to smell. Shrieks with me at every tiny bunny we’ve ever been lucky to see peeking its head out of the grass. She’s always commenting on how we’re so small in the grand scheme of things, and isn’t it so mindboggling?

This is all to say that she is good at being a mother. So much so that I lean in, and my body dissolves into giddy joy, whenever I get a look into her not as a mother, but as a small girl.

As a mother, she is the feeling of home, embodied in her strong, warm thighs—spiky after a shave—that I’d cling to as a child. She is who I’d see start to bite into a tart Granny Smith apple and, before she could finish, would ask for a taste myself. Even then, I could never believe how she’d offer it to me—offer anything, her shirt as a napkin, her meal as my own—without an eye roll or a hint of disappointment that not even a whole apple could be hers. I still think of that with every bite of every apple I take, I can tell you that. I stare at the shiny fruit and I, again, wonder when all of that “happens.” If it just “happens.”

Even now, when we’re grown and seated around a restaurant table, barely a moment after the server has placed her meal down hot on the table, she’ll begin cutting it into pieces for us to try. Now, when we’re grown, we groan in unison and say, “Mom! Eat your food!” She’ll see the last untouched bite of the appetizer, no matter how small or cold, and will begin slicing it into equal parts for all of us, and we’ll immediately go, “Mom! Just take the whole olive, my god!!” She deserves every last piece of every last appetizer, but she’d never believe it. In all of her fork-and-knife divisions, I can see that she feels, with every moment that she is breathing, that we are still the same as her body; growing and turning inside of her, eating from her, with her, because of her.

Because of that, I find myself grinning with a dopey kind of joy when she tells me about her favorite breakfast as a girl. No fork or knife in sight, no belly but her own. Her Granny made the very best porridge, she tells me. Full of cream-top milk and surely, a few big pinches of sugar. Pleasure for me begins with appetite, it’s why I’ve asked about her favorites. And I hear her tell me about her afternoons too, between hockey, or art, and how delicious her relied-upon sandwich always tasted—peanut butter and marmite, swiped on soft slices of bread, and stuffed with nasturtium leaves from the garden. And again I find myself grinning so wide. Trying to picture her, maybe with her legs curled up on a seat in the kitchen, in her detested green school uniform, devouring the sandwich whole. I beam because this human I don’t know; and how could that be possible when she is me and she is also everything?

I try to picture her, I try so hard. But I can’t know her and I never will. I can take all the visions I’ve heard described—her, young and very afraid of what might be under the bed at night, resolving to leap in one long, brave stride to the door to run to the bathroom; her, smoking a first cigarette from behind the cover of a banana tree—and try to conjure up a girl. A place, a world away. But I can’t, really. It’s too hard. I’m left to lean against the countertop late in my twenties and ask her to tell me, once again, about the Sunday family meals, and how her brother baked his bread. How she swirled passionfruit syrup—granadilla syrup—into her water and how she thought that was the tastiest drink in the entire world.

Only then can I try my best to put all I know in a jar and shake it all up in my brain. The girl who guzzled that drink down and asked for more; the young woman, just married, who dunked bread or was it french fries into the broth of the bouillabaisse in France I’ve heard reminisced on my entire life; the mother who helped us set up for tea parties, allowing us to plop one sugar cube each into our thimble-sized teacups and sip the sweet, milky nectar that couldn’t possibly be considered tea. The same, the one, magnificent human being.

But still, I’ll never, really, be able to see the scope of it all. Maybe one day as a mother myself. But this isn’t a letter about trying to understand the scope of a girl becoming a woman becoming a mother—my mother. Oh no, I need at least two or three more decades to try to make sense of all of that.

This letter, simply, is about all of the bits and bites that I’m able to get.

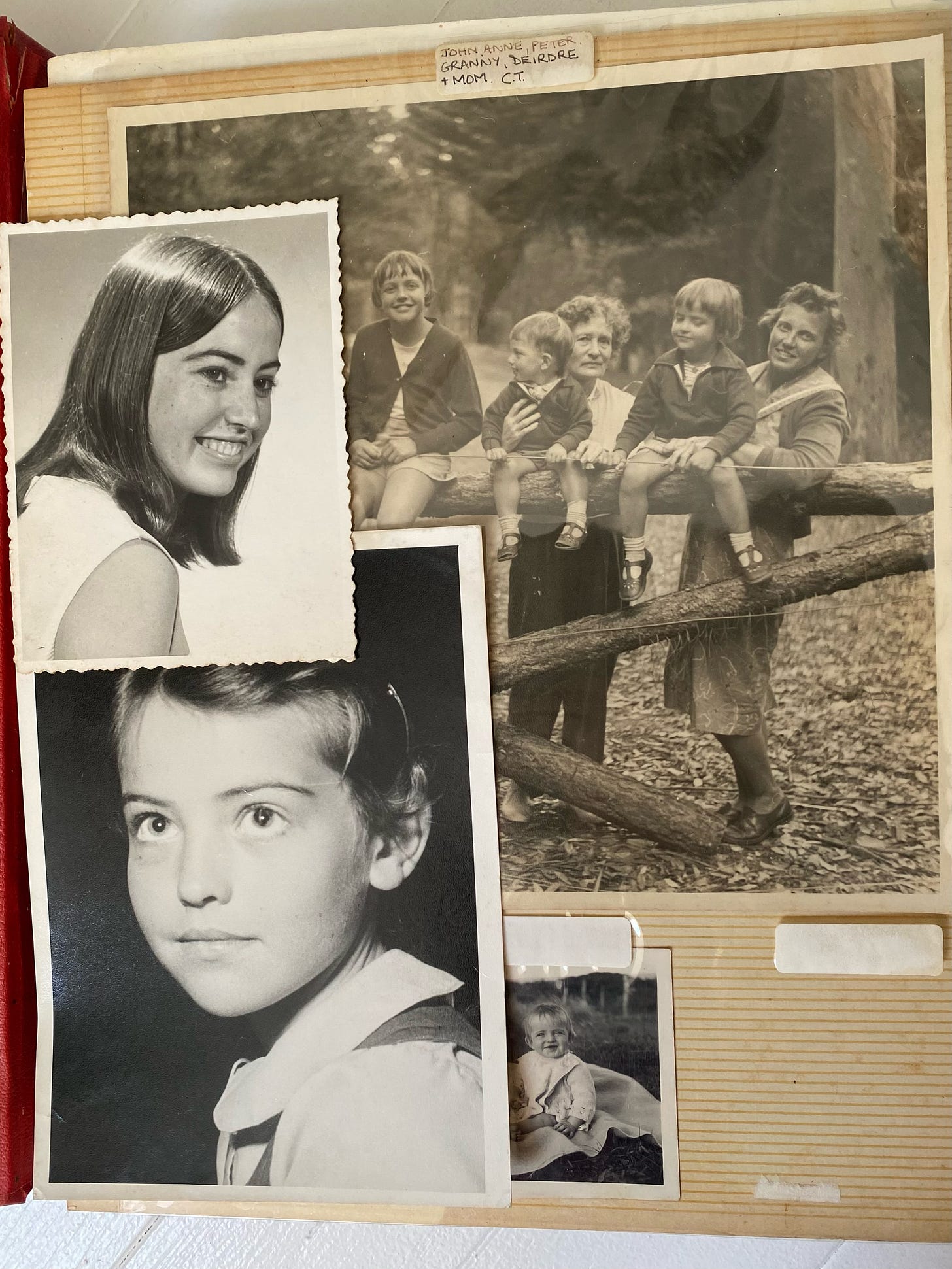

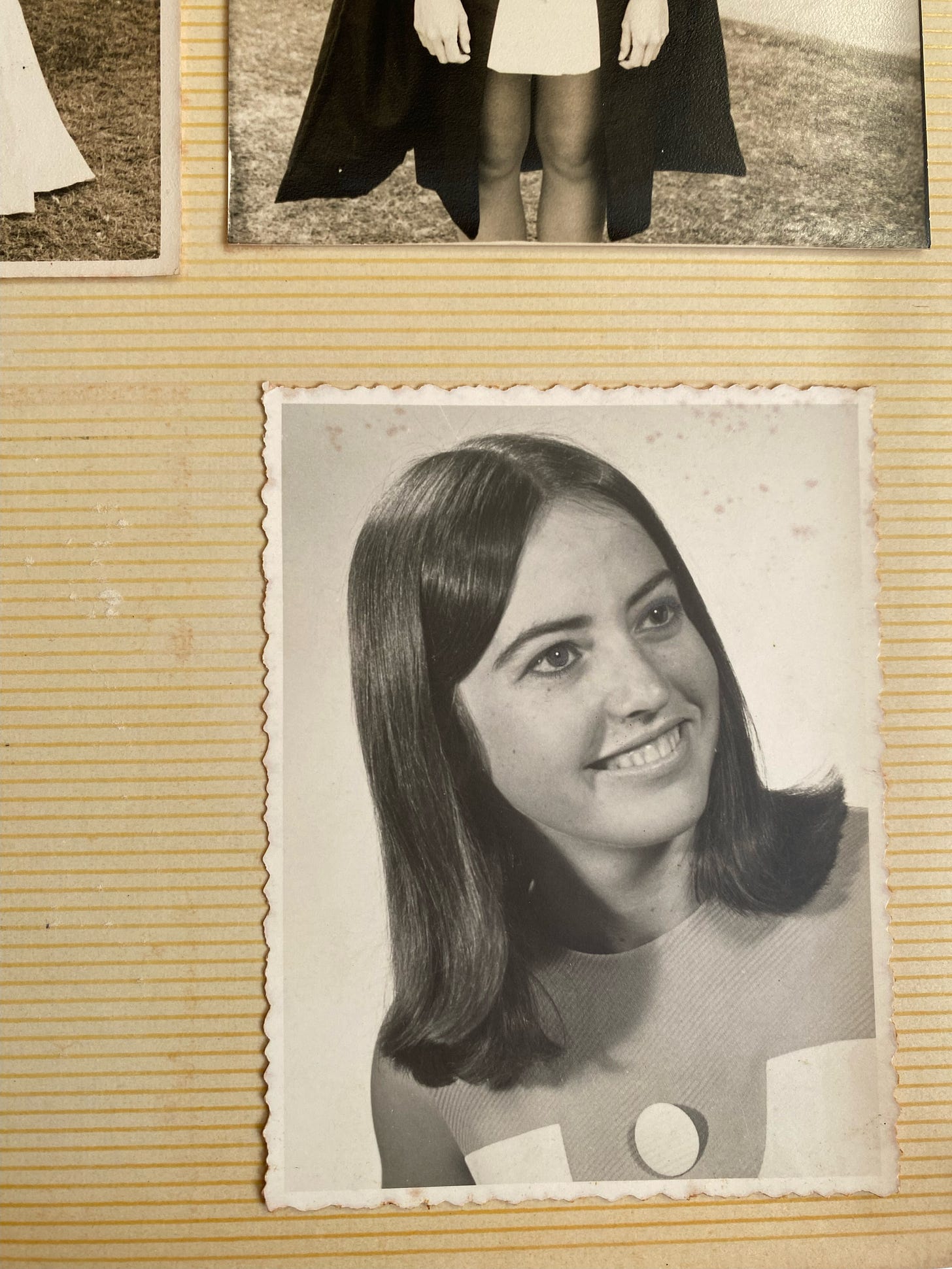

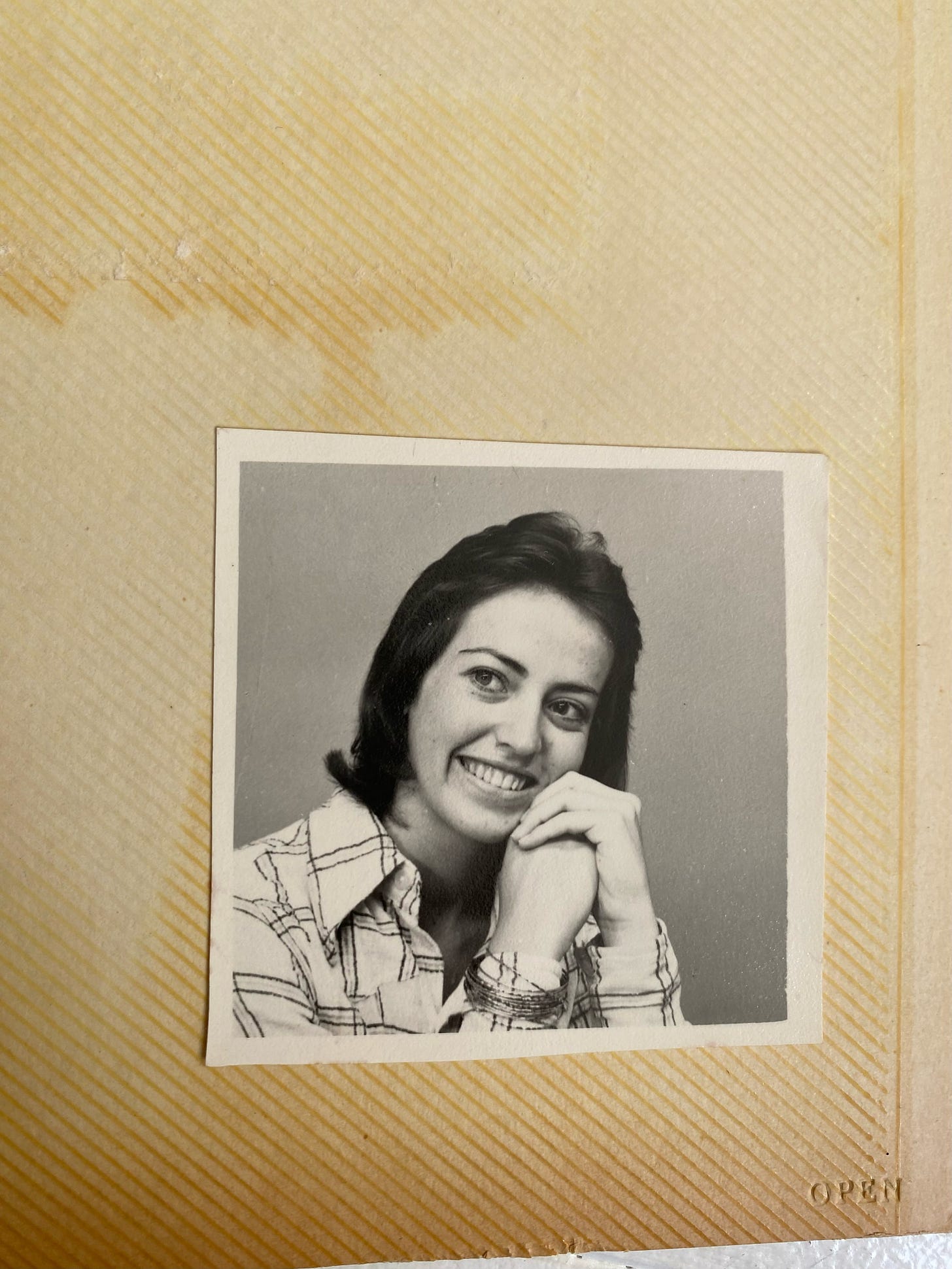

With every crumb, every image, every haircut I look back on in the pages of dusty albums (Mom, do you also measure your memories by the changes of your hair?), I’m offered more of her. With every delight and pleasure and moaned-after taste she’s ever allowed for herself, and also offered to everyone else in every room, I’m shown more of her. From the very base of her heels tangled into the earth, to the tips of her fingers that she uses to smear paint and smudge charcoal and mop up and slurp the last of any plate’s remaining sauce. And I can tell that she, mother, child, cloud of pigment, flower, root, is everything that has ever been alive.

My beautiful mama, between Harare and Cape Town and England and her garden in Maryland where she is always crouching, picking at weeds, dragging a hose, and complaining about the lack of rain. My mama, who emails in reply to every newsletter; who printed out every single page of written work from the blog, and put it in a binder so that I could see the words made into a book in front of me. I am the luckiest girl.

MADI 😭😭😭

This is beautiful 🫶🏽